Author: Filipe Carvalho, Associate

It is a rule in Brazilian law that generally whoever alleges must prove the allegation. Pursuant to article 373 of the Brazilian Civil Procedure Code[1], the burden of proof rests on the claimant, to prove the constitutive facts of their case (item I) and on the defendant, to prove facts impairing, modifying or extinguishing the claimant’s right (item II).

Therefore, every time the party files a proceeding, it must indicate[2] and gather[3] in its statement of claim all the documentation that proves its allegations.

However, there are situations in which this burden of proof rule cannot be applied, citing as an example, where a claimant does not have the evidence to fulfill this duty or because it is easier to obtain proof of the contrary fact.

In this sense, the Brazilian Procedural Code[4] authorises the judge to assign the burden of proof in a different way, provided that he does so by reasoned decision, and the judge must also give the party the opportunity to discharge the burden that has been assigned to them.

It is worth mentioning that the Brazilian Civil Procedure Code (Federal Law No. 13,105/2015) also grants the parties the right to define, before or during the process, the distribution of the burden of proof[5]. This rule does not apply, however, if it impacts a party’s inalienable rights (one that cannot be given or taken away) or when it makes it excessively difficult for a party to exercise that right.

In 2018, the Superior Court of Justice (STJ), a collective body of the Brazilian Judiciary, edited Precedent n. 618 which has the following wording: “The reversal of the burden of proof applies to the proceeding of environmental degradation”.

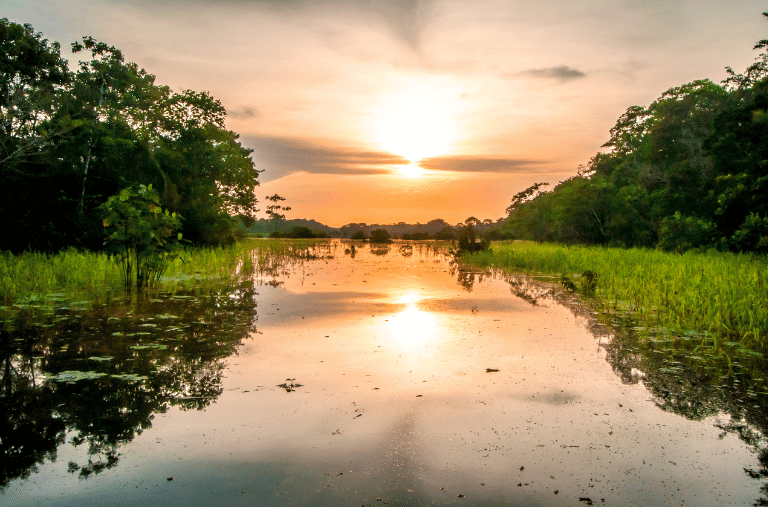

The reversal of the burden of proof in environmental matters can be justified by the application of the precaution principle, in the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED 1992) principle 15 which states that: “In order to protect the environment, the precaution principle must be widely observed by States, according to their capabilities. Where there is a threat of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing effective and cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation[6].”

In simple words, if there is any suspicion that an activity may cause environmental damage, the environment must have the benefit of the doubt.

Not surprisingly, the STJ, when ruling on an environmental case[7], established the understanding that “the precaution principle (…) presupposes the reversal of the burden of proof, transferring to the concessionaire the burden of proving that its conduct did not give rise to risks to the environment (…)”.

In fact, the same understanding has been put forward again by the STJ[8]. See: “the precaution principle presupposes the reversal of the burden of proof, and it is up to those who allegedly caused the environmental damage to prove that they did not cause it or that the substance released into the environment is not potentially harmful”.

It is concluded, therefore, that the existence of these rules, supported by solid case law, are focused on preventing the activities of large polluting companies from going unpunished, bringing to the party (which is often underprivileged) effective parity of weapons and a balanced means of substantiating claims, either by themselves or by using the reversal of the burden of proof.

References

[1] Art. 373. The burden of proof is assigned to:

I – the plaintiff, as to the fact constituting his or her right;

II – the defendant, as to the existence of a fact that impedes, modifies or extinguishes the plaintiff’s right.

[2] Art. 319. The complaint shall inform:

VI – the evidence with which the plaintiff intends to prove the truth of the alleged facts;

[3] Art. 320. The complaint shall produce the documents that are indispensable for the filing of the action.

[4] Art. 373, §1º: In the cases provided for by law, or in view of the peculiarities of the action relative to the impossibility or excessive difficulty of performing the duty pursuant to the head provision, or even the greater ease of obtaining evidence to the contrary, the judge may assign the burden of proof differently, provided this is done in a reasoned decision, in which case the party must be given the opportunity to carry out the assigned charge.

[5] Art. 373, § 3º: A different assignment of the burden of proof may also occur by agreement of the parties, unless:

I – it impacts on an inalienable right of the party;

II – it renders the exercise of the right by one of the parties excessively difficult.

Art. 373, § 4º: 4 The agreement referred to in § 3 may be executed before or during the proceedings.

[6] It is worth noting that the precautionary principle has its origins in the “World Charter for Nature”, of 1982, whose principle n. 11, “b”, established the need for States to control activities potentially harmful to the environment, even if their effects were not fully known.

[7] STJ, AgInt in the Interlocutory Appeal in Special Appeal n. 1311669 – SC, Judge Rapporteur Ricardo Villas Bôas Cueva, judged on 03 December 2018.

[8] STJ, REsp 1.060.753/SP, Judge Rapporteur Eliana Calmon, judged on 01 December 2009.